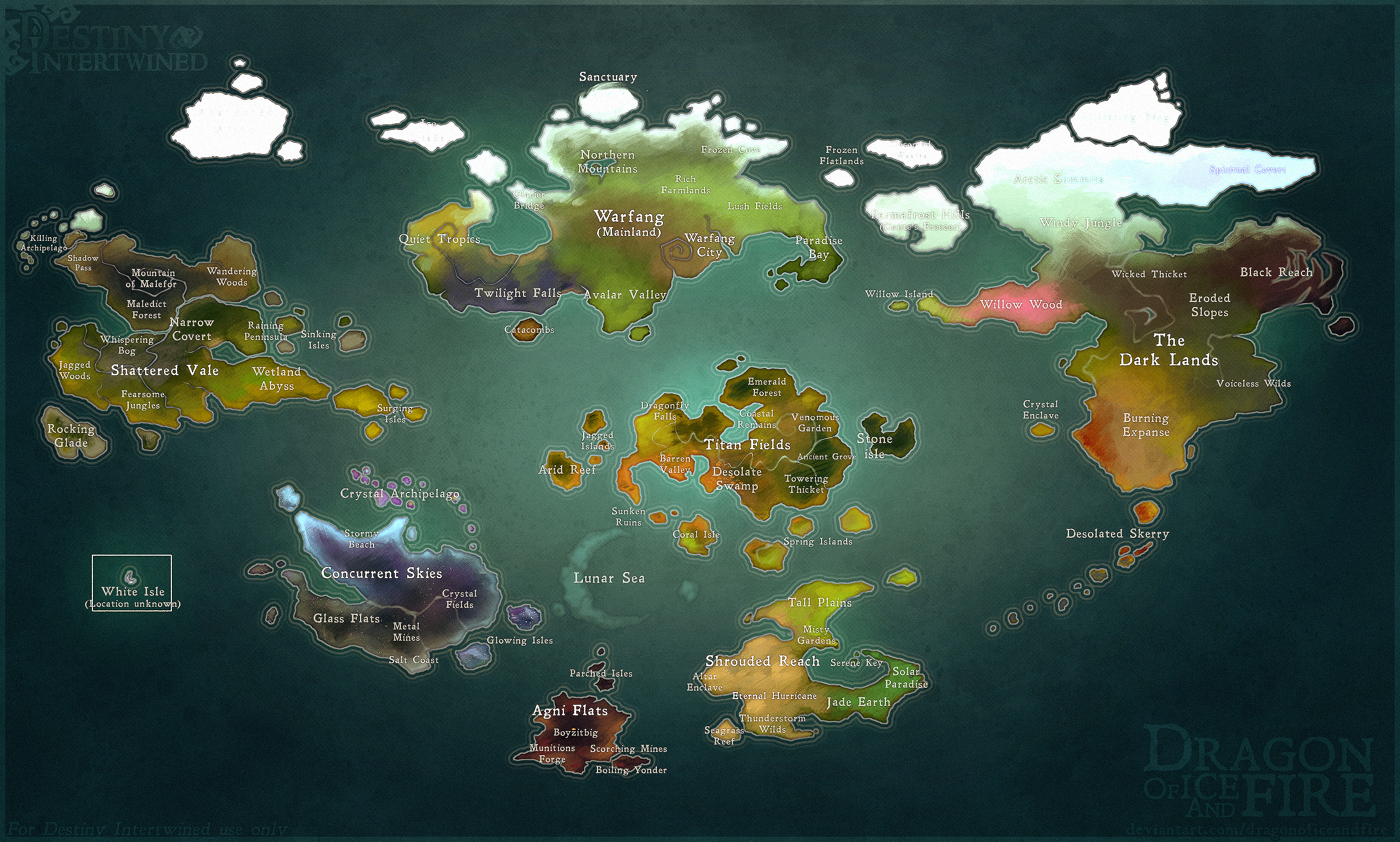

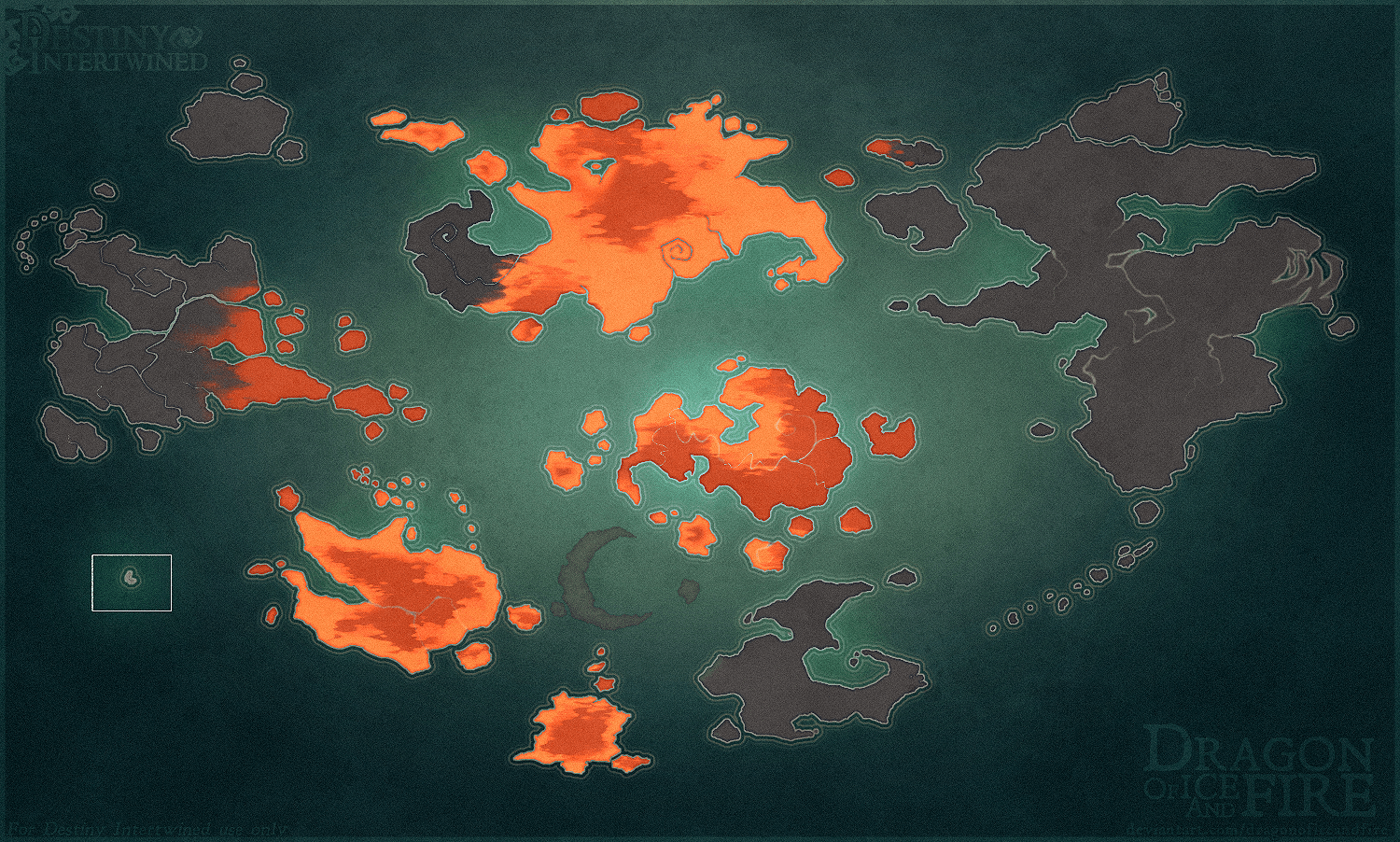

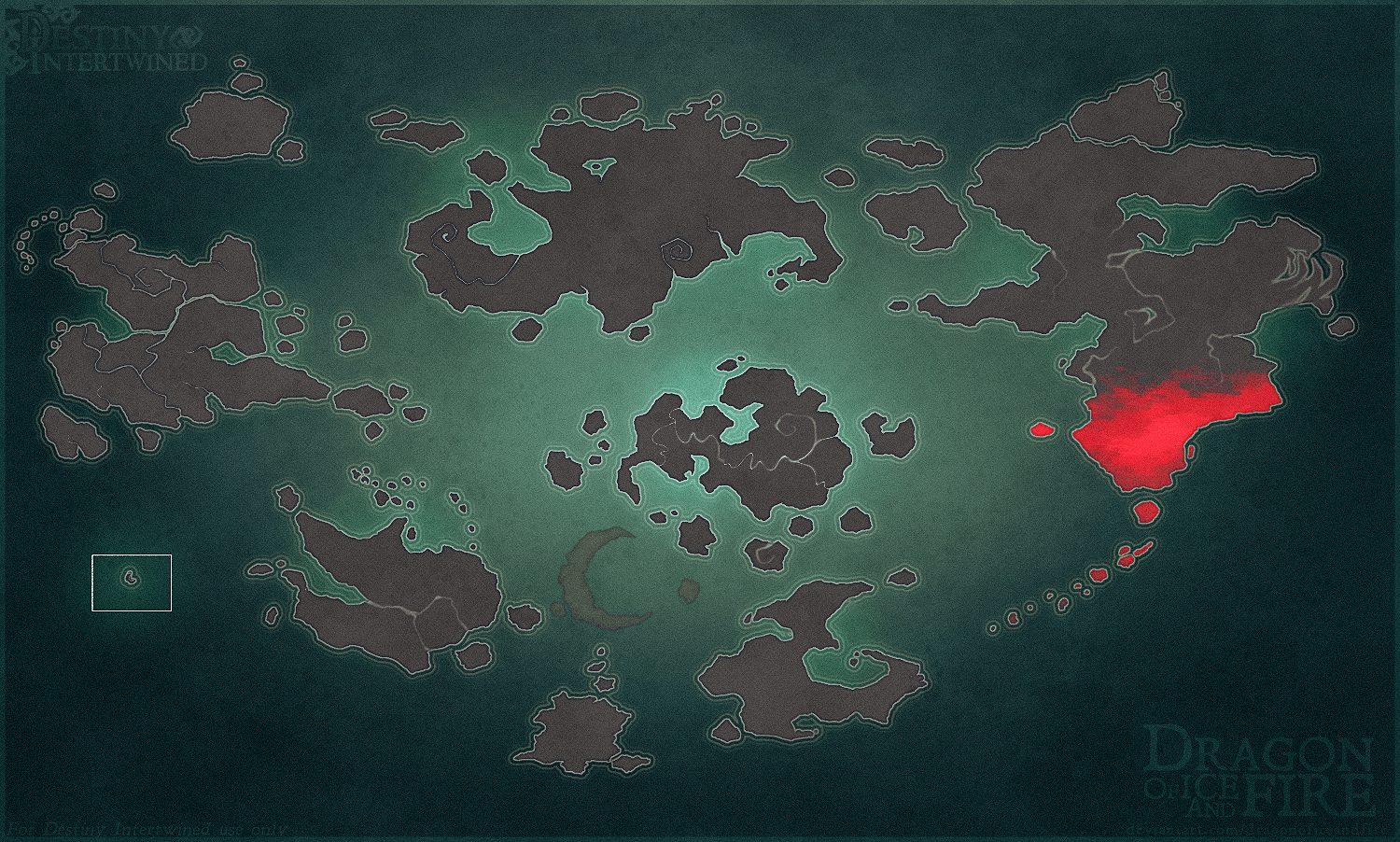

Dragons are widespread in the Realm, having originated from several of the major landmasses and spread to others.

Dragons live in the following areas;

❖ Warfang Mainland (Primarily Fire, Electricity, Ice, and Earth dragons)

❖ Ice Citadel, Northern Mainland (primarily ice dragons)

❖ Titan Fields (Primarily fire and earth dragons)

❖ Concurrent Skies (Primarily electric dragons)

Much of Concurrent Skies is barren and not suitable for dragon inhabitants, thus quite uninhabited. This island is primarily inhabited for mining operations.

❖ Agni Flats (primarily fire dragons)

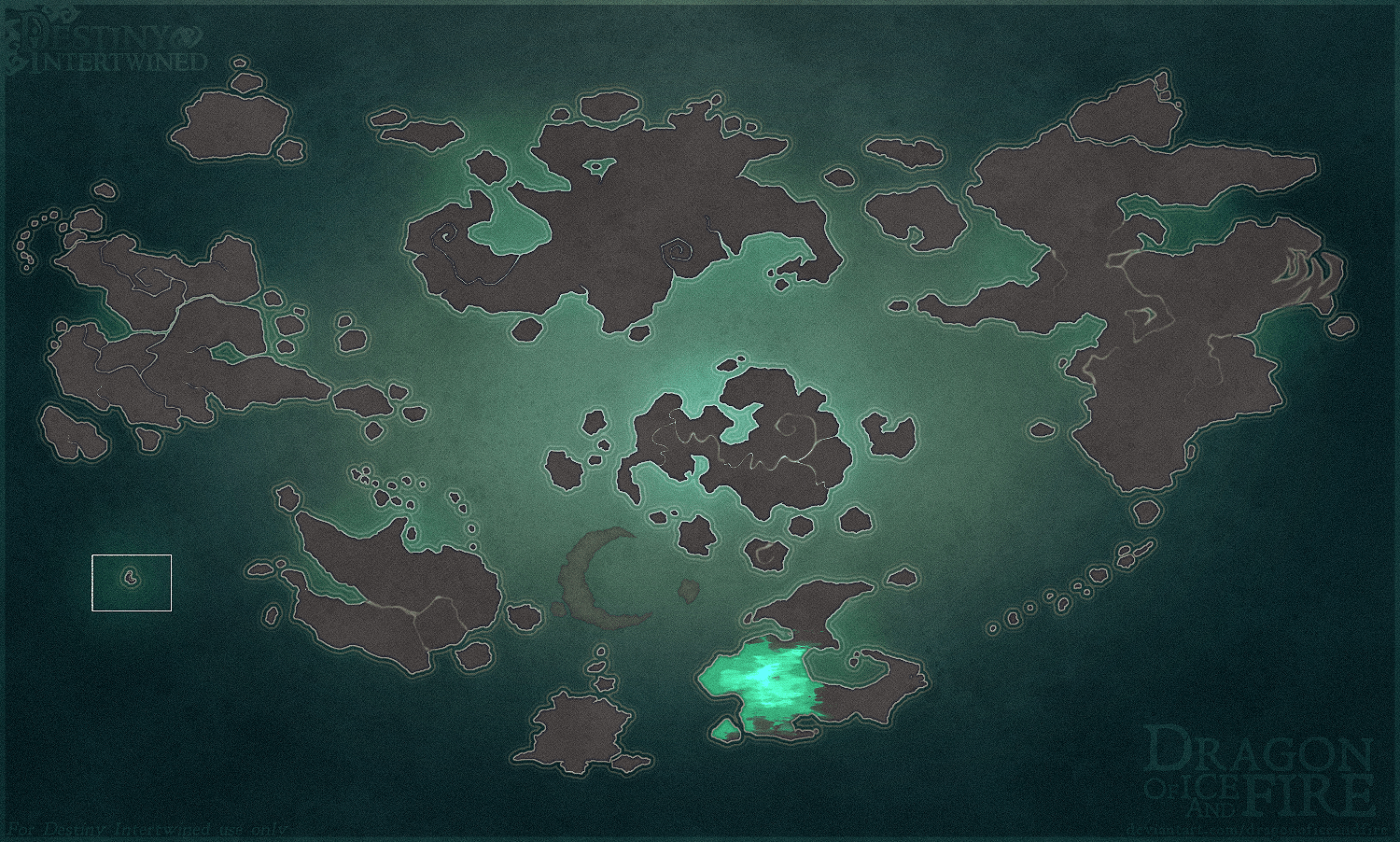

❖ Lunar Sea (exclusively water dragons)

Areas with primarily or exclusively military presence; Abandoned Arctic, Sanctuary, Shattered Vale, Frozen Flatland, Venomous Garden, Ancient Grove, Towering Thicket, Desolate Swamp.

❖ Eternal Hurricane (almost exclusively wind dragons)

Much of the Shrouded Reach is not inhabited by dragons save for areas beneath the Hurricane and small settlements in the west. These areas have heavy pirate and raider presences and are unsafe, thus they are not well settled.

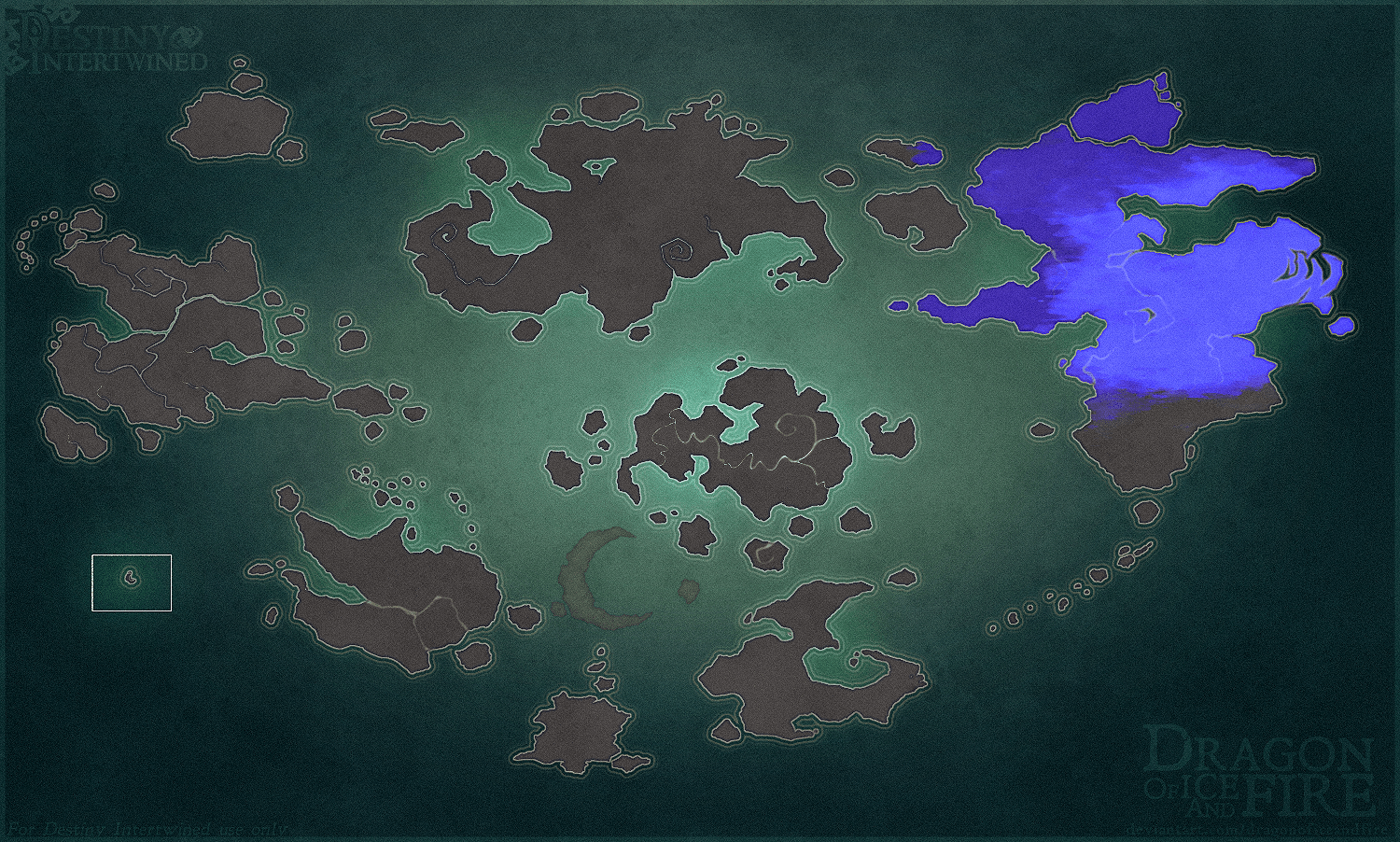

❖ Farsanct (dark dragons)

❖ Southern Lawless Lands (dark dragons)

Dragons can live up to 200 years, with an average life expectancy of 150 years (when counting only cases of death related to old age, such as health complications). Many dragons die young, especially children and newborns without access to healers, bringing an overall life expectancy much further down).

They have 7 stages of life.

After around 3 months of gestation, a dragon lays its eggs, and the hatchlings within will continue to develop.

At birth, the egg shell is somewhat soft, but will quickly expand and harden, becoming quite thick.

Around six months after an egg has been laid, the hatchling within will start to break free. If this happens much sooner, due to damage to the egg or the hatchling being premature, this can cause risk to the hatchling’s life as they are not done developing.

A premature hatchling can take much longer to develop than others, or even have problems that persist through their whole lives.

On the opposite end, some dragon eggs are known to wait for decades to hatch. While eggs may ‘intuitively’ wait for better conditions to hatch (to certain degrees, the hatchling is able to sense winter weather, heatwaves or drought, and will wait to hatch to increase their odds for survival, up to several moons if necessary) some eggs wait so long, they are believed to have been affected by ancestral intervention. They have been given special purpose, and must wait for a certain point in time to hatch. This is extremely rare, happening only a few times every 500 years.

Damage to an egg or a weak hatchling may delay the hatching for up to three more moons. In these cases, a healer may be needed to free the hatchling, otherwise the hatchling will die.

A dragon is considered born when they hatch. At hatching, dragons are very physically independent. They learn to walk within moments, and are known to be able to hunt and kill critters for food (though this carries a significant risk for them, so they are normally raised and fed by their parents and family).

New-born dragon hatchlings operate on instinct, with intelligence and social ability developing later through nurture. Most hatchlings can talk by the age of 3, with some learning as early as age 1, or as late as 6 years.

7.5 years old is the average age of element discovery. At this age, some children learn to fly (mostly electric and wind dragons), although their small wings only allow for brief sustained flight.

Children of other elements are capable of flight usually around age 10, with earth dragons learning the latest at age 12 due to their weight and smaller wing spans. However, water dragons living in bodies of water can go their whole lives without ever learning to fly.

Dragons enter their teenage years and start hitting puberty. Physical growth increases fast. While dragons can be sexually mature at around age 18, it is uncommon for them to reproduce until 30 and after, as the chances of pregnancy are strongly diminished until they are old enough for a safer pregnancy and birth.

This is thought to be rooted in the species being able to reproduce very early in times of extremely low population numbers, although this bears risks for the dam who, despite being almost half the size of a physically mature dragon, has to birth eggs of almost normal size.

After reaching sexual maturity, dragons spend another 30 years growing into their full size.

At around the age of 50, a dragon’s physical growth stabilizes, and they will not grow much taller.

At the age of 120, a dragon is considered an elder, though dragons will normally not be slowed by age until around age 170. Most dragons do not make it to this age, and it’s not uncommon for dragons to live long enough to become elders at all.

At around the age of 170, elder dragons will slowly fall behind and suffer the ache of old bones, lose weight, and possibly lose reproductive and mental functions. While they can push on until the maximum age of 200, most dragons that are healthy and have access to high quality food and healthcare, die from old age in the 170-180 range.

Genetics are usually the deciding factor of whether or not a dragon can push to 200. Natural causes of aging can kill dragons before the years start to show, such as heart and organ problems or conditions of the brain.

You can view a comparison between dragon ages and human ages here.

Dragons are a quadrupedal, hexapodal species; they walk on four limbs, with an additional two limbs for flight. All limbs have three digits each, with only the forepaws having thumbs, which are opposable. Their forepaws are reasonably dexterous, allowing them to hold and manipulate objects, enough to be able to write. Each digit of their paws are tipped with a claw.

The digits of their wings are connected by a thin membrane; the dorsal and ventral sides are exactly the same. They will have rather long tails in proportion to their body, with some variation in said length. Wings can similarly vary slightly in size, however this is locked to one’s element.

Their bodies are covered in scales, never fur or feathers, with bare skin only being exposed by scarring. Texture, size, and shape vary widely, such as the tough padding on their paws.

Fat and muscle, when able to be built (often gatekept by ready access to food), are typically going to pack around the neck, sides, base of the tail, biceps, and haunches.

Nearly all dragons are physically, visibly influenced by their elements, down to their colorations prominently matching that of their variant’s very hues.

Body decor (made of cartilage, bone, and webbed skin) such as frills and spurs are also strongly influenced by Element, often taking on mimicry to aspects of an element or its nature- for instance, the faux feathers of Wind dragons or false leaves of Earth dragons. Decor is not dense to the point of inconvenience to the dragon’s range of motion, nor is it minimal enough to only be found on one location of a dragon’s body.

Most apparent markings are similarly attuned to Element–flicks of flame or bolts of electricity, to name a few, will adorn the body, most often along the shoulders, thighs, and face, but can appear near anywhere on their scales and wings, sometimes other areas as well such as horns and plates.

While some traits from mixed elemental heritage may be visible (certain amounts of green on Fire dragon indicating a recent Earth ancestry, whiskers appearing from a Wind ancestry, ect), a dragon will dominantly take on the traits of their Element.

A dragon’s main scale color is defined by the color taking up the most of their base body coloration (not including decor, horns, plates, claws, or wing membranes) and will be used when broadly describing a dragon, even if they are not monochrome. (i.e a Red dragon, a Blue dragon, ect)

Dragons are typically duochromatic, and at most trichromatic, but even monochromatic dragons can have a large variance in saturation and brightness of their hues. The specifics of colors’ appearances will often be up to the dragon’s element- a Fire dragon’s blue, for example, will usually be more vibrant than that of an Electricity dragon’s blue.

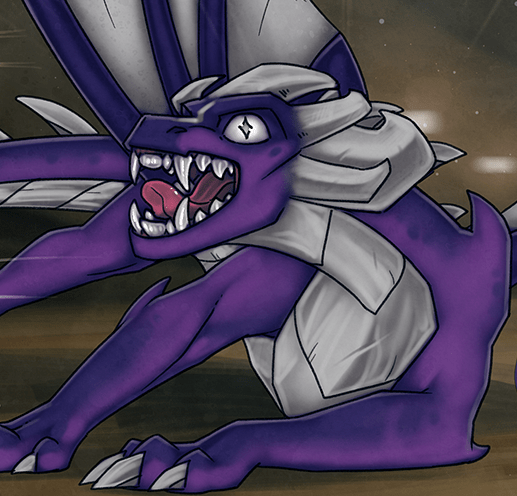

Purple dragons were unheard of before Malefor was born in the year 3000, though the significance of this scale color is not yet known. Prophecy says only one purple dragon will be born every ten generations – about every 500 years.

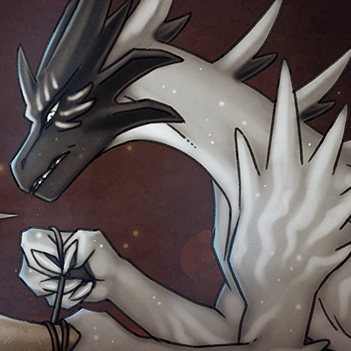

White dragons did not occur before the year 2500, at the birth of the first Scions Aether dragon. White dragons are the result of almost a millenia of strictly and systematically crossing every primordial and derivative element to create a dragon whose blood is so elementally mixed, their element is decided at the toss of a die. All current white dragons descend from the first, Izar, and due to the clan’s breeding pattern – which they keep strictly secret – no other lineage has produced a white dragon.

Black dragons were not seen before the artificial Elements – the Dark Elements – were created. While black scales are more often associated with Shadow dragons due to their equally black Elements, black as a primary scale color is possible for Fear and Poison dragons as well, as this scale color is tied to other factors. A dragon without a dark element will never have a black main scale color.

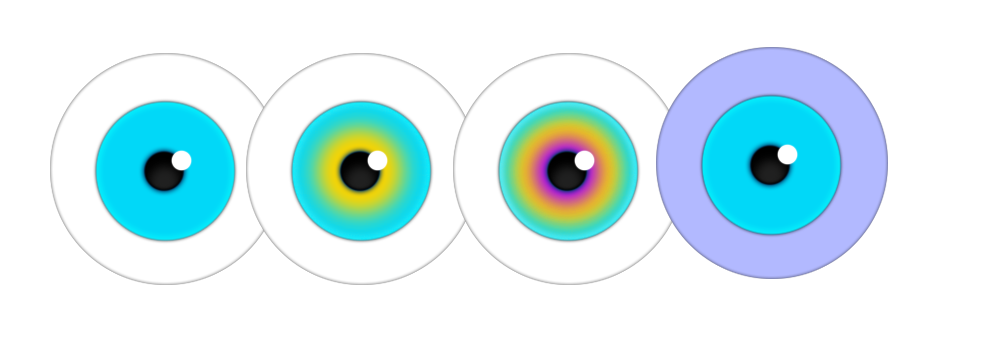

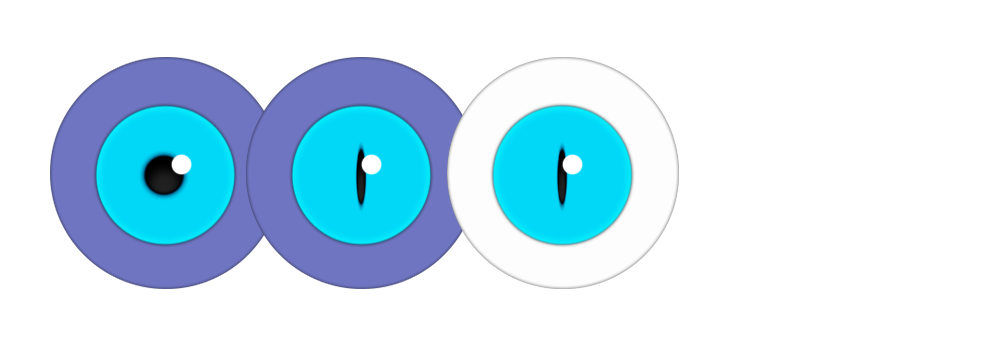

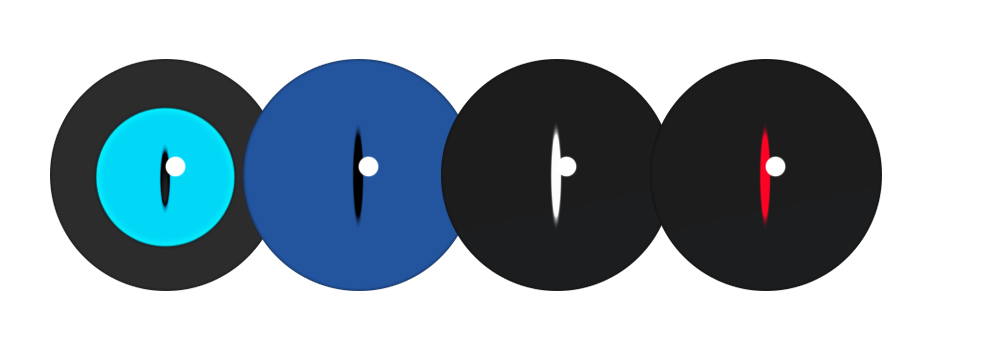

Dragon eyes are a trait only affected in Element by whether one has Dark Dragon heritage, but will mostly follow the same general structure, with a pupil, iris, and sclera. All irises can only have a maximum of three tones; heterochromia of all types (sectoral, central, or complete) is not uncommon. Pupils will dilate but shape is only changed by heritage, either rounded, or slit (which, when dilated, become more of a diamond shape).

Dragons without Dark Dragon heritage will always have rounded pupils and white or pale colored sclera.

Displaying half-blood eyes. While slit pupils with mid-tone sclera exist on pure dark dragons,

the other examples are exclusive to half-bloods and dark variants.

Dragons are an omnivorous species, able to consume numerous forms of vegetation and meat, including raw meat, with relative safety. Their teeth will be lost and regrow throughout their lifetime–missing teeth are often temporary.

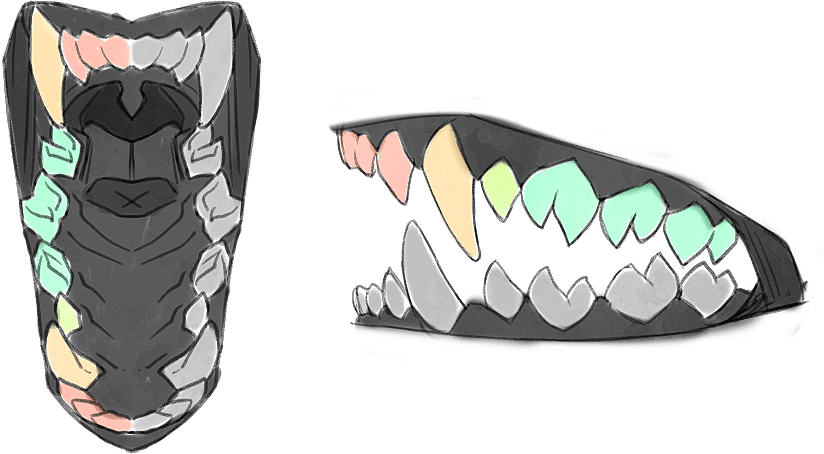

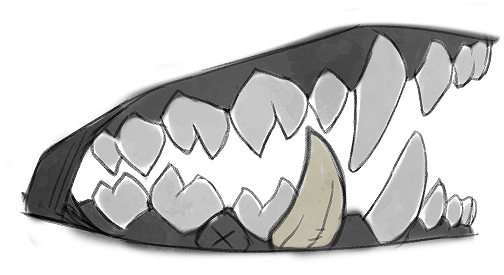

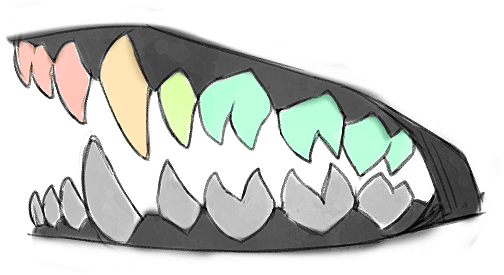

Primordial and derivative dragons always have bony pale teeth- 12 Incisors, 4 Canines, 4 Premolars, 12 Molars.

Their canines do not vary significantly in length but if they grow at an ‘incorrect’ angle, the dragon may have a snaggle tooth.

Dragons with the earth element, or with recent earth heritage, may have tusks. These are not actually teeth, but a spur growing from within the mouth. As such, tusks do not resemble teeth, but rather the other spurs on the dragon.

Tusks do not get bigger than as shown, and grow only from the bottom jaw, in front of the premolar, or between the first and second molars. Rarely, a dragon may have tusks in both these spots, but one set will be smaller than the other.

Dragons with the water element who have spent generations living in the sea have developed sharper, more even-lengthed teeth, useful for holding on to prey underwater. Non-water dragons descending from these may have ‘hybrid’ teeth, but it will gradually fade away and disappear after three generations.

These teeth do not occur in first or second generation water dragons, or in water dragons who have lived primarily on land, regardless of generation.

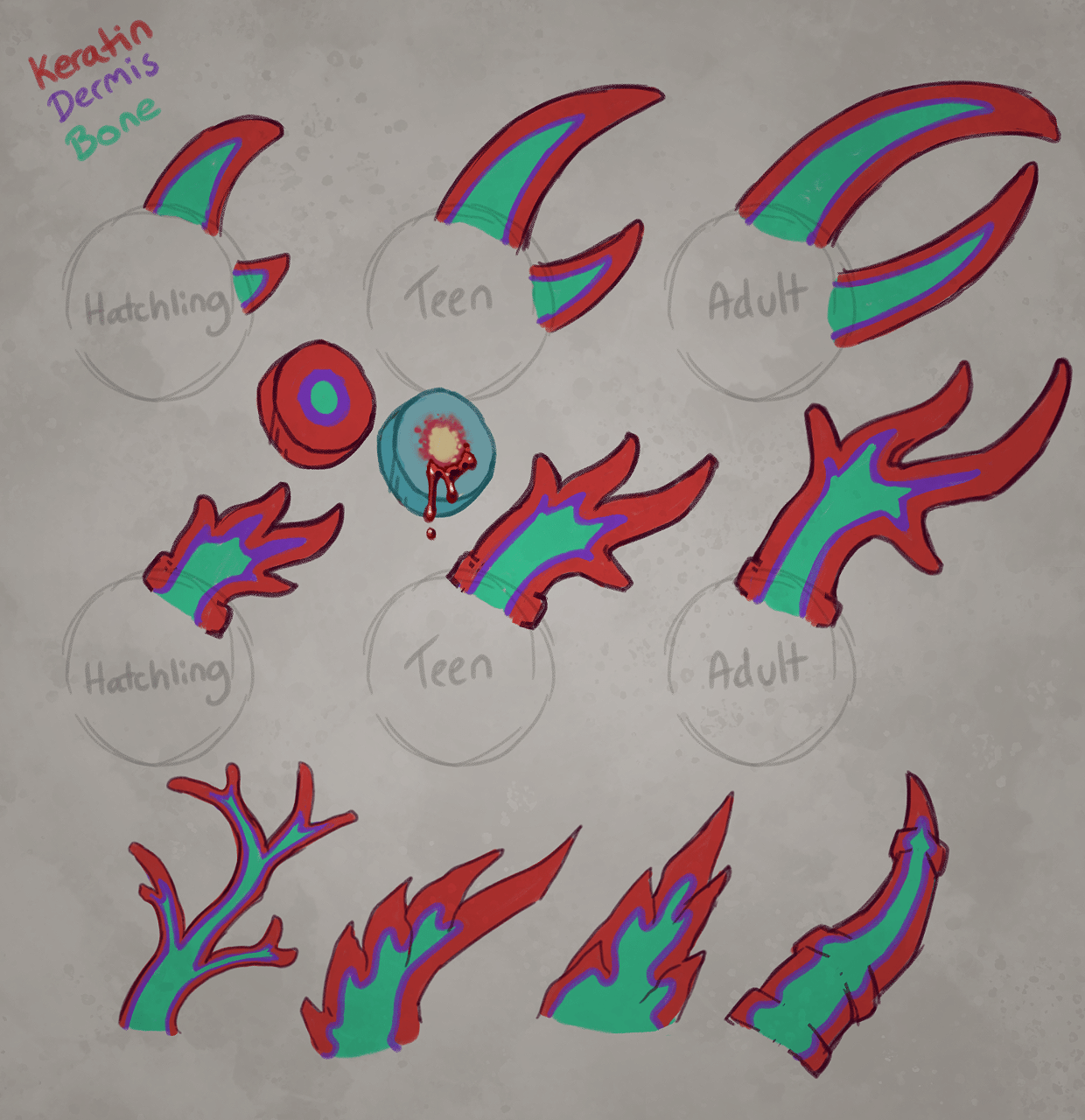

Horns, and by extension claws, have three layers–a keratin-like layer, a dermis layer, and a bone layer. The dermis contains nerves and blood vessels that allows the horn to grow larger and more complex with age. A dragon can bleed quite a bit from a damaged or severed horn, but it is generally not life threatening. The dermis also allows parts of the horn that do break off to regrow, albeit slowly. The regrowing horn or horn piece may not look as it did before, in shape or quality, which is more likely the older the dragon is, and is also affected by the quality of their diet, stress levels, etc.

Most horns have a thick keratin layer, and branches may be entirely keratin. Thinner branching horns, such as that of “antler” horns, will actually have the dermis retract once the branch has fully grown, leaving only bone and keratin. This gives them the advantage of not being as easy to break, but should the branch break off, they will be unable to regrow.

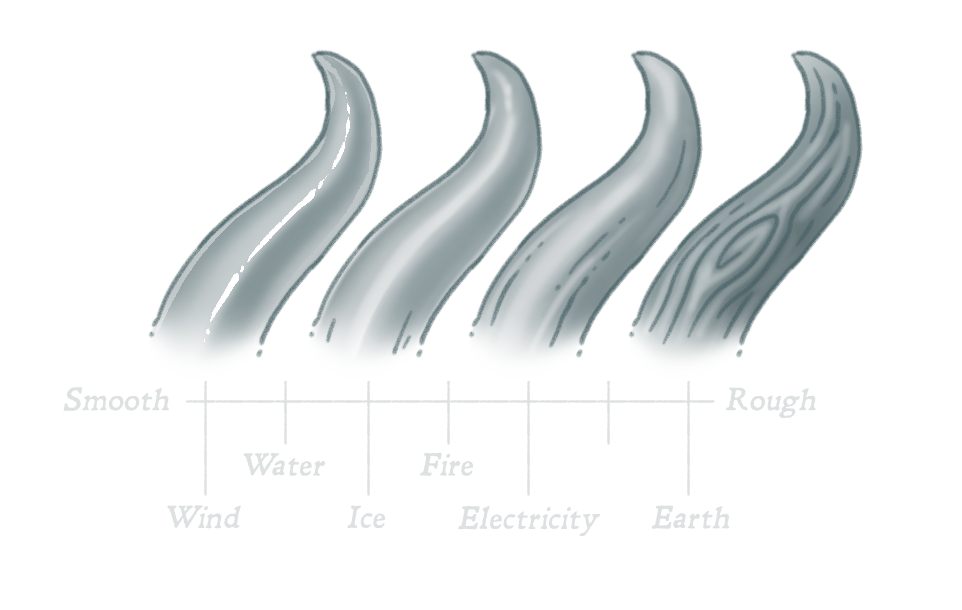

The keratin layer, on top of having the capacity for being any color, has a wide range of roughness. It can range from smooth and shiny, like polished metal, to rough like wood. A dragon will have a specific texture to their keratin, which is reflected all over their body (they will not have wood textured horns and shiny claws–their claws will be similarly rough and matte).

Body spurs work similarly, but they do not have bone in them, as they grow from the skin and do not attach to the main skeleton. Only horns grow from bone.

Most dragons have plating along their stomachs: a natural, added protection to some of their most vital organs. Typically, it will cover from just below the chin, extending to the end of the tail. It will often have segmentation, with thicker plates in particular needing to be segmented in order to allow movement. The edges of plates and their segments vary highly in shape, but will always repeat their pattern. The density of plates will also affect the texture–thick plates will be rougher in texture, thin plates will be smoother.

Stomach plating will often bear scratches which will not bleed (as it is not living tissue) and may fade over time, but traumatic enough wounds can result in long-term holes and gaps, exposing the softer scales underneath. If an injury goes too deep and scarring forms, this section of the plates will not regrow. If magically healed, the keratin will grow out again, but the mark of the injury will persist for years, if not decades.

Plating can also show up on other parts of the body, including along solid decor such as horns and spurs. These plates will typically blend into the scales of the body, with the patterning remaining consistent across all appearances

The main scale color of a dragon is indicative of not just their element, but often the hue of their element. Every color is possible for dragons, with special exceptions for purple, white, and black.

Purple dragons were unheard of before the first purple dragon, Malefor, was born in the year 3000, though the significance of this scale color is not yet known. Prophecy says only one purple dragon will be born every ten generations – about every 500 years.

White dragons did not occur before the year 2500, at the birth of the first Scions Aether dragon. White dragons are the result of almost a millenia of strictly and systematically crossing every primordial and derivative element to create a dragon whose blood is so elementally mixed, their element is decided at the toss of a die. All current white dragons descend from the first, Izsar, and due to the clan’s breeding pattern – which they keep strictly secret – no other lineage has produced a white dragon.

Black dragons were likewise not seen before the artificial elements – the dark elements – were created. While black scales are associated with shadow dragons, they are quite common in all dark dragons, hence their association with darkness. A dragon without a dark element will never have a black main scale color.

Secondary and tertiary colors (non-scale colors) can be any hue and any shade. These colors will correspond to the element colors if the main scale color does not.

Dragons can be divided into three groups based on their coloration; monochrome, duochrome, and trichrome.

Monochrome dragons only have one hue on their bodies, for example blue. They may have blue scales, light blue horns and plates, and dark blue wings, but because the hue of these colors are all blue, they are considered monochrome. (example; Vitreus, Incendis)

Duochrome dragons have two different colors on their bodies, for example blue and green.

(example; Hayze, Lynerius, Therris, Amberius, Malefor)

Trichrome dragons have three different colors (example; Terin, Jordhin)

Colors are defined by color groups; black-grey-white, pink-red, orange, yellow, green, blue, purple. A dragon can only have max three of these color groups. Eye color does not count toward color groups, so a monochrome blue dragon may have red eyes and still be considered monochrome.

The natural base (scale) colors of fire dragons are red, orange, yellow, blue, and pink. Fire dragons do not have mainly green scales if their element is not green fire.

Fire dragons are colorful. Their palettes will generally lie around very saturated, mostly mid-tone colors. Fire dragons tend not to have very desaturated colors.

The secondary colors (on horns, plates, membranes, or elemental markings) of fire dragons have more variety, but purple and green are rare, both signs of ice and earth impurity respectively. Fire dragons tend not to have secondary or tertiary colors that are very or completely desaturated, this includes black or white, but may have dark and bright, highly saturated colors. They don’t combine dark colors with bright/pale colors, as this kind of contrast is an electric trait.

Fire dragons may have smooth or rough horns, plates, and claws, but generally lean more in the middle.

Fire dragons favor frills over spurs, meaning they will usually have frills growing instead of spurs.

The natural scale colors of electric dragons are orange, yellow, and blue. Electric dragons are contrasting. Their primary, secondary, and tertiary colors will come together and make a mix of bright colors and dark colors. As such, electric dragons tend to look paler, more desaturated than fire dragons.

Commonly their secondary colors will be dark and often desaturated, like metals or stormclouds (unless their base color is dark, then their secondary colors will be pale). As such, electric dragons aren’t colorful like fire dragons, but bearing a mix of washed out brights and darks. Their elemental markings are often colorful, however, as these tend to display the element color. While electric dragons may be light grey, they are rarely dark grey or a mix of grey and black, as this is not usual and really only seen in Stormbringer dragons.

While electric dragons with red/pink and green electricity may have these as primary colors, they tend not to be primary colors unless the dragon in question possesses these variants. Even those who do may still only have the natural base colors, and have their element color in their markings. Electric dragons with purple electricity will naturally not have a purple base color, instead one of the natural base colors.

Electric dragons usually have semi-rough horns, plates, and claws, but smoother texture is not rare.

Electric dragons favor both frills and spurs, often sporting both.

The natural scale colors of ice dragons are blues and light greys. Ice dragons are bright in their coloration, and in general do not have very dark markings or colors. Their scale colors are usually be blues and light blues or light greys, or less commonly darker but saturated blues. Ice dragons are never a saturated red, orange, yellow, or green base color (if heavily mixed, these colors may appear albeit desaturated). At most they may be aqua or pink, but most will be blue, blue-grey, or light grey.

Other colors do not exist in their base colors because they are nonexistent in ice variants. As such they tend not to appear as secondary or tertiary colors either. Ice dragons can have purple secondary colors without having purple ice or purple ice heritage.

Pure desaturated black markings and secondary colors on ice dragons without dark blood are a result of fire or electric mixing, and is rare. It is very rare for ice dragons to have colors not represented by their element variants, so the presence of these colors on an ice dragon suggests recent impurity.

Ice dragons overwhelmingly have smooth textured horns, plates, and claws, giving way for a shiny, ice-like appearance.

Ice dragons favor spur growths over frills.

The natural scale colors of earth dragons are browns, tans, and greens. Earth dragons tend to be mid-tone to dark in their scale colors, though a light color is not too uncommon. They can have any level of saturation but don’t get too grey, even with grey earth (which itself is never 100% grey, but tinted).

An earth dragon’s secondary color is usually still a shade of brown or green, but due to the versatility of multicolored earth, all colors are possible for an earth dragon’s secondary color. It’s not impossible for an earth dragon’s base color to be red, yellow, blue, or pink, but these will be more muted. If the earth dragon’s base color is not one of the natural colors, these will appear as secondary or tertiary colors.

Earth dragons generally do not have black secondary colors, and white is very rare. While they can have dark or light colors, these should be saturated, but not over-saturated unless green or brown.

Earth dragons overwhelmingly have rough textured horns; theirs being the roughest, most wooden-like horns among dragons. Smooth, shiny horns are quite uncommon.

Earth dragons favor both frills and spurs, often sporting both.

The natural scale colors of wind dragons are grey, cold-tinted greys, and teal. Wind dragons tend to be mid to light colored and generally don’t contrast like electric dragons do. While most wind dragons will have a scale color aligned with the natural base colors, the colorful variants of wind allows for any other non-purple base colors, though this is uncommon. Wind dragons can have any secondary colors, usually still mid-tone to light, rarely dark colors.

Red, orange, and yellow are the rarest colors on wind dragons. While wind dragons may often have one saturated color (usually markings), wind dragons consist of mainly desaturated/grey colors.

If the wind dragon’s base color is not a natural scale color, these colors will be present as secondary colors.

Wind dragons overwhelmingly have smooth, shiny horns, plates, and claws. Rough, bulky horns are very rare and if they occur, suggests a heavy Earth lineage.

Wind dragons favor frills over spurs.

Half of wind dragons have whiskers, long symmetrical growths from the face that seem to almost float in the air, and the wind dragon has limited control of these. They are not prehensile. Whiskers are made of a soft cartilage and have a consistent thickness between individuals, never too thick or thin. Whiskers are always tipped with a small frill if the dragon has frills. Whiskers originate in wind dragons but they may pass them to non-Wind descendants for a few generations. Whiskers will disappear if the wind genes get too diluted.

The natural scale colors of water dragons are aqua/teal and blue. Water dragons can be dark, mid-tone or light colored, but are generally quite saturated. Due to the fire root of the water element, water dragon base colors can sometimes be warm, though this is uncommon. They may more commonly have any of these colors as secondary colors, though much of the dragon will be blue hues, as the water element comes only in blue colors. Water dragons are capable of limited bioluminescence. Their elemental markings (not other markings) will glow in water when there is insufficient light. This will happen subconsciously but will ‘deactivate’ if the dragon is afraid or tense, so as to not attract predators.

Water dragons will always have webbed paws.

Water dragons can also have barbels, which are similar to wind whiskers but are much shorter, can occur in pairs, and are not tipped with frills.

Water dragons usually have smooth horns, plates, and claws, but can also have semi-rough textures.

Water dragons favor frills over spurs.

Dragons spend a lifetime growing from tiny newborns into massive adults, growing nearly seven times their original height at birth by the time their bodies finish developing at age 50. Their size is influenced both by their bloodline and their Element, with the derivative Elements (Wind and Water) skewing smallest and Dark Elements being significantly taller. The average among non-dark dragons is roughly ~5.5 meters, with averages within the elements hovering roughly around this size.

Outliers to these obviously exist, such as individuals with Dwarfism. These dragons are only roughly 2.5m – 3.5m in height as adults, not much taller than a late teen or young adult, but their proportions often give away their condition: their heads, paws, and wings are noticeably larger, while their legs are visibly quite short. Mobility suffers a bit, but the greatest risk is to dams who have a heightened pregnancy risk, most notably becoming eggbound.

On the other end of the spectrum, there are those with Gigantism. Their bodies grow very quickly, able to achieve a height of 7 meters at 20 years old, but at a significant cost to their health and lifespan, their bones unable to keep up with the rapid growth. They will be unable to fly, and struggle to walk – most with gigantism pass away by 30, with none exceeding past age 40.

Dragons often start courting and having relationships in their teenage years, but are incapable of reproduction until around the age of 18. It’s uncommon for dragons to have children under the age of 30 due to the decreased odds of pregnancy and increased risk, but it’s not unheard of. Dragons can have children until the end of their lives, but advanced age (170+) can impair their ability to carry and sustain eggs and other reproductive functions.

Male dragons can reproduce at any time, but will experience a monthly hormonal spike that encourages reproduction. Female dragons have a monthly cycle as well, with a fertile window of up to five days. They do not lay unfertilized eggs – once a pregnancy begins, the fetus is formed first, then is enveloped by a tough shell a few weeks before being laid.

Gestation lasts three months, and it takes at least six months for the egg to hatch – however, ancestral involvement can prevent an egg from hatching for years, decades, even centuries if needed. No matter how long it takes, the potent magic within dragon eggs will keep a hatchling alive until the right time.

Gravid dragons may start experiencing ‘morning sickness‘ type symptoms at the beginning of their pregnancy, and at around halfway through gestation (5-7 weeks) they will experience rough ‘magic sickness’ with similar symptoms. This occurs due to the surge of magic to the developing fetus(es), which affects the dam. Her element/magic will become briefly stronger, but often hard to manage. The sudden increase in magic often causes nausea, vomiting, headaches, and bouts of energy followed by exhaustion. This stops latest at 15 weeks, when the eggshell has hardened enough to contain the magic.

Clutches average at two(36%) to three(15%) eggs per clutch. Single-egg clutches are common (33%). It is possible for a clutch to be up to eight eggs, but this is extremely rare(0.2%).

From conception to around the 13th week, a dragon fetus develops without a shell, instead growing inside a permeable sac with a yolk feeding it nutrients. After the 13th week, the walls of the sac begin to harden, becoming a tough shell over the next few weeks. The fetus becomes cut off from its surrounding, free-flowing nutrients, and becomes dependent on its yolk.

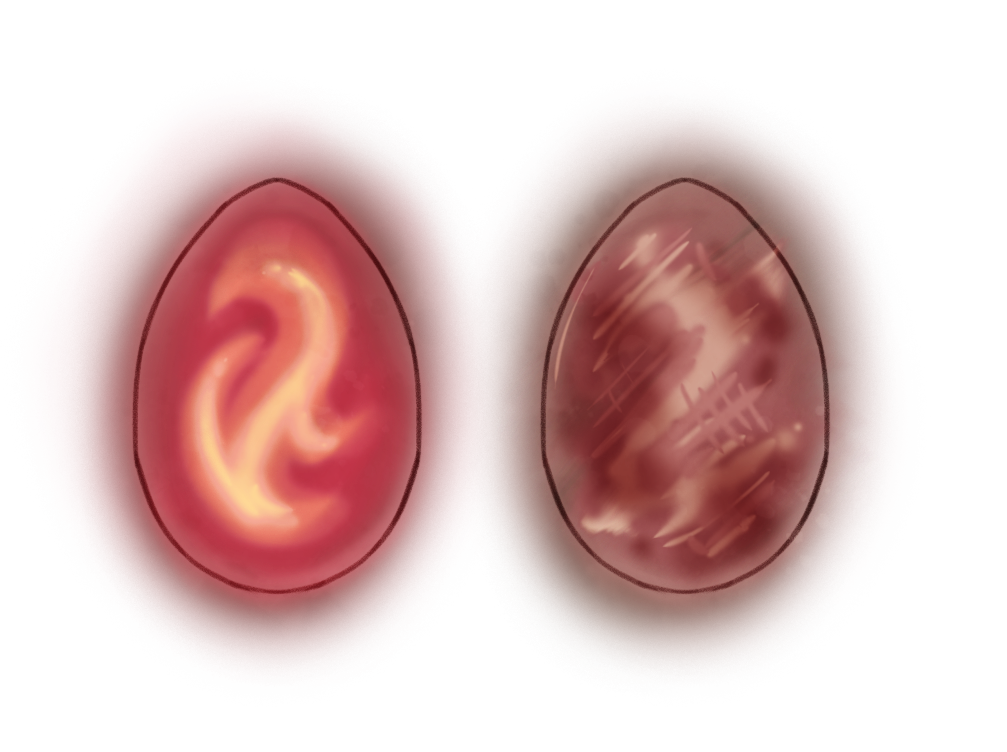

Around the 16th-17th week, the egg is laid. If all is well, the egg is colorful and reflects the dragon’s element. The fetus itself however is still translucent and without scales or elemental attributes.

Over the next 6 moons, the fetus grows to the bounds of its shell, developing scales, tiny claws and horns, and a little bit of wing membrane. Much of the time spent in the egg is magical development; the dragon’s spirit binding to the physical body and infusing it with its element, coloring their body, and working in tandem with the biological genetics to drive the dragon’s appearance to suit and survive their element.

There are various challenges and complications that can impact a dragon’s reproduction.

It is uncommon, but possible for a female dragon at the end of her teenage years to become gravid, as dragons reach sexual maturity at this age. This is believed to be an adaption to harsh and long gone times when dragons may not have lived long.

Still, this is risky for the dragoness, as at this age their egg to body ratio is significant and becoming eggbound is common. Egg binding is when the dam is unable to lay her eggs.

As hatchlings are able to be independent moments after hatching, an eggbound dam is not an end to the lineage (and thus not a concern, from an evolutionary standpoint). Dragons have legends of clutches of living, healthy eggs being discovered amidst the bones of their late dam. Dragon eggs are relatively sturdy, and will wait for the safest time to hatch – forever, if they must.

But this is strictly a need for extinction-based scenarios. Dragons will otherwise instinctively avoid reproduction to, earliest, after their last growth spurt which happens between ages 18 and 26, or most ideally after 30 when they are nearly their stable height. At this age, egg binding is much less common (unless the dam is naturally very short).

Egg binding can happen at any age and size because of mineral and/or hormone deficiencies, and poor health. Hormone deficiencies can cause weak contractions preventing laying.

Sometimes, egg binding can be solved without invasive methods, such as with supplements (especially for minerals that make up the eggshell), massages, hydrating, lubricating, or just waiting. In some cases, magic can help, but there is no healing spell that can directly affect egg binding, neither do healing crystals, as egg binding is not injury. Egg binding is a death sentence without intervention.

If all else fails, the eggs have to be removed. This can be done by destroying the egg from the outside and pulling the pieces out (which has its own risks for the dam, being internal injury and internal rot, so this is not practiced by knowledgeable healers – it also kills the would-be hatchling), or cutting the dam open, pulling the eggs out, and immediately closing the wound with excess healing gems before the dam loses consciousness (at which point, she will be unable to call the gems to heal her, and she will die, as most healers will not have the power to heal an opened abdomen fast enough.

Unfortunately, the shock of being cut open while awake, and with little to no anesthetic, can also prevent a dragon from calling healing gems, also leading to death.

It is unfortunately common for dragons to wind up in debt due to seeking emergency help in egg binding situations, and having to repay healers the cost, even just for the healing gems. This is regardless if the dam (or the egg(s)) survive the ordeal.

Deaths from egg binding are naturally far less among clans and high to middle society, whom have access to healers and preventative care (from rare herbs, advanced magic, plentiful magic gems, to plain good diet (and the knowledge of what makes one) and clean facility).

While egg binding is a risk to the dam, there are numerous risks to the eggs themselves to consider.

It is worth noting that young dams have significantly decreased fertility until the point where a pregnancy is safer. The odds for a pregnancy to start are low, and the odds of a pregnancy staying viable are also low. The younger/smaller the dam is, the smaller her clutches will be – often only one egg at a time.

This low fertility can and will respond to certain environmental stressors, wherein the dragon’s fertility will rise if it seems they won’t live long enough to have a safer pregnancy. At the same time, other stressors will make a pregnancy harder to begin or maintain, such as excess physical exertion and recurring injury (such as from war or abuse). Early miscarriages will go physically undetected.

If a pregnancy makes it to term and eggs are successfully laid, the risks are not over. During the 6 month minimum the eggs need to incubate, the hatchling within the egg may die. At times, they may be laid already dead – this being clear by the state of the egg. Healers can detect a declining egg, but often be powerless to do anything about it.

Eggs can die for a multitude of reasons. A common one is genetic or developmental failures leading to the fetus being unfit for life, or environmental reasons, such as ice eggs being in high temperature environments for too long. Other reasons can be tied to the dam, such as poor diet, poor health during pregnancy, damaged ovaries/womb, premature laying, or back to back pregnancies.

They can also die due to their own poor health, which can be due to the above reasons, or on account of being the ‘runt’ of their litter; wherein their clutch sibling(s) hogged resources before they developed shells – this being more common in larger clutches. The runt’s shell may have been incomplete or weaker, allowing for damage or infection, or they simply lacked adequate nutrients in their yolk.

Rarely, eggs can die due to magic exposure; their own. The hatchling dreaming within the egg discovers their element far earlier than what is safe, and not being able to control it or prevent themselves from being hurt by it, will die by it. This usually happens very fast, and is over before the egg’s guardians can detect the newly discovered magic. Theoretically, an egg could survive if the magic is drained in time, and continuously drained, to prevent the fetus from harming itself with their element.

Overall, dead-in-shell eggs happen in about 1 in 4 to 1 in 8 eggs. This ratio is affected by dam health and circumstances. On average, dams between 20 to 60 and 150 to 200 experience more dead-in-shell eggs, and it is also more common for first time dams. Genetics will also play a part; some lineages being more prone and others less.

An egg with the same complications that leads to dead-in-shell eggs can still make it to hatching, but the hatchling may die later. This can happen in the first two to three years. The hatchling will start out weak and/or decline over time. Depending on the cause, it is possible to save them, but they may carry lifelong complications such as disabilities. Damage to the egg can lead to death, or disabilities if healed in time.

Other causes of infant/hatchling mortality are usually illness, then injury and natural death (like predation). Once a hatchling turns 5 they are considered to be out of the danger zone.